The Post-war ‘Incidents’ in the Royal Canadian Navy, 1949

Richard H. Gimblett

The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) entered the year 1949 with a certain degree of optimism. It had ended the Second World War as the third largest Allied fleet, but within a year demobilization and retrenchment had reduced it to a mere rump of five ships and barely 5,000 men. Recognizing the enormity of the challenge of rebuilding the post-war fleet virtually from scratch, the Assistant Chief of Naval Personnel predicted bleakly that ‘the training service will be our most important function for the next five years’. [1] Three-and-a-half years later, in February 1949, senior officers of the RCN saw themselves ahead of schedule. Overall strength had been raised to just under the authorized 10,000-man peacetime ceiling, so that, in addition to the aircraft carrier Magnificent and the training cruiser Ontario, a total of six destroyers were in commission. Although none of these could boast full complements, finally there were sufficient hulls in the water to conduct meaningful fleet exercises. For the navy’s spring cruise of 1949, the Pacific and Atlantic squadrons were to combine for fleet maneuvers in the Caribbean Sea for the first time since the end of the Second World War.

|

1. HMCS Crescent departing Esquimalt for China, February 1949. (Source: National Archives of Canada) |

Then it all unraveled. On 26 February, during a fueling stop at Manzanillo, Mexico, 90 Leading Seamen and below of the destroyer Athabaskan — over half the ship’s company — locked themselves in their mess decks in a sit-down strike, refusing to come out until their collective grievances had been heard by the captain. Two weeks later, on 15 March, 83 junior ratings in another destroyer, Crescent, staged a similar protest. Ported in Nanjing, China, in support of the diplomatic community during the final stages of the Chinese Civil War, they were unaware of the previous incident. But news was now spreading through the fleet. Within days, on 20 March, 32 aircraft handlers in Magnificent briefly refused to turn to morning cleaning stations as ordered.

Each of these incidents was defused almost immediately, with the respective captains entering the messes for an informal discussion of their sailors’ grievances. Still, something was evidently wrong in the Canadian fleet. Since the sailors had offered no hint of violence, no one used the charged word ‘mutiny’. Indeed, in Athabaskan, the captain was careful to place his cap over what appeared to be a list of demands, so that no technical state of mutiny could be said to exist. But the ‘incidents’, as they came to be called, constituted a challenge to the lawfully established order of the navy and warrant the term ‘mutiny’. Having transpired in suspiciously rapid succession, they seized the attention of a government and a nation growing sensitive to the spread of communist influence. A communist-inspired strike in the Canadian merchant marine in 1948 sparked fears of subversion in the naval service — indeed, the Liberal government had only just withstood charges by the Conservative leader of the opposition that the federal bureaucracy was overrun by communists. Prime Minister Louis St Laurent was planning a general election for June 1949, and wanted this latest specter of the ‘red menace’ also put to rest.[2] The Defense Minister, Brooke Claxton, ordered a commission of inquiry to investigate the state of the navy.

The Liberals went on to win the election, and the commissioners presented their deliberations in November 1949 in a volume famous henceforth as The Mainguy Report.’ Its trim length of 57 pages notwithstanding, this remained for nearly 50 years the most incisive examination of a military institution to be undertaken in Canada.[4] The report exposed the hardship of general service conditions, described a number of factors critical to achieving good officer-man relations, and outlined a blueprint for reform. Its impact was immediate and the report deserves its description as ‘a remarkable manifesto’ and ‘a watershed in the Navy’s history’.[5] Still taught to new recruits of all ranks, and the continuing subject of staff college analysis, the report’s findings, recommendations, and conclusions remain a potent legacy.[6] The year 1949 is remembered as the one of crisis and reform in the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN).

That does not mean, however, that that legacy is all it is presented to be. This chapter will demonstrate that, for all of the universal truths contained in The Mainguy Report, the claims ascribed to it (and, by extension, to the year 1949), and just about everything else we supposedly ‘know’ of the mutinies in the RCN in that year, except for the facts of their occurrence, are mistaken. The incidents of February and March 1949 occurred for reasons more complex than a simple breakdown in officer-man relationships. In fact, what the report does not adequately reflect are the enormous strains of demobilization and the restructuring of the new peacetime navy.

Labor historians have shown that workers tend to strike not to gain some new right, but to recover something lost or threatened. In this there are obvious parallels to naval history, where there is ample evidence to suggest that ‘mutinous acts remain fundamentally loyal to the status quo of the service’.[7] This certainly was the case in the series of strikes by the communist-dominated Canadian Seaman’s Union (CSU) in 1946-48, which the Liberal government perceived as the model for discord in the RCN. Indeed, trouble in the merchant marine flared again in April 1949, just as the Mainguy Commission prepared to sit. But where the CSU was fighting for better pay and benefits for its members, and against efforts by the shipping companies to break the union,[8] in the Canadian naval incidents, as suggested by Crescent’s captain, ‘It will be noted that [the] three [conditions] previously considered as all-important; food, pay and leave; are not mentioned. They are eminently satisfactory in the RCN.[9]

What, then, was the status quo in the RCN in 1949, and what had occurred to upset it? What had been lost or threatened that the sailors felt compelled to recover through mass insubordination? There was then and is now little disagreement over the initial finding of the commission: that there were no communists in the RCN. It was the subsequent litany of ‘General Causes Contributing to [the] Breakdown of Discipline’ that implied the navy’s post-war morale problems were the fault of an uncaring officer corps harboring aristocratic British attitudes inappropriate to the democratic sensitivities of Canadians. If the commissioners found no organized or subversive influences at work in the naval service, they identified such systemic problems as the breakdown of the divisional system[10] of personnel management (which they attributed to lack of training and experience of junior officers), frequent changes in ships’ manning and routines with inadequate explanation, a deterioration in the traditional relationship between officers and petty officers, and the absence of a distinguishing Canadian identity in the navy (as opposed to one described as still too closely linked to the Royal Navy). The commissioners laid special emphasis upon the failure in each of the affected ships to provide functioning welfare committees, as prescribed by naval regulations, to allow the airing and correction of petty grievances.[11] They noted also an ‘artificial distance between officers and men’, with the clear implication that this was the result of Canadian midshipmen obtaining their early practical experience in the big ships of the Royal Navy.[12]

None of these ‘General Causes’ should have been the stuff to inspire mutiny, even in its restrained Canadian form of mess-deck lock-ins. Reading the report and the volumes of testimony from which it was prepared, one is struck, as were the commissioners, by the banality of the men’s grievances and their difficulties in articulating them.[13] Neither the absence of welfare committees nor the men’s lack of higher education can fully account for the acts of indiscipline or the men’s poor attempts at explaining their actions. The spontaneous nature of the incidents and the lack of coordination point to other discrepancies. If the motives for dissension were as widespread as the commission implied, the wonder is not that three ships mutinied in 1949, but that the rest of the fleet did not join them. At the same time, the coincidental timing of the incidents, despite the spatial separation, certainly led the Minister and the Naval Staff to presume collusion, and yet none was found. So we are left with two intriguing questions: were the incidents somehow connected?; and why did they transpire at the precise moment they did in 1949?

The authors of The Mainguy Report acknowledged that, during the Second World War and in its immediate aftermath, the RCN had ‘grown and shrunk in a manner unparalleled’, from a pre-war total strength of 1585 officers and men to a wartime peak of over 93,000, and back down to the 1949 total of 8,800.[14] They blithely asserted that the ‘stresses and strains ... accompanying ... every such process ... need no verbal comment’, and then proceeded to detail the breakdown of the RCN in the late winter of 1949, as if the service had suddenly dropped at that moment to the bottom of the pit. Brief mention was made of an incident in the cruiser Ontario in August 1947, but it was attributed entirely to the character of the ship’s executive officer and was considered significant only because the participants were later spread among other ships.

The truth is more complex. The Canadian Navy of 1949 was very much the offspring of the service that had fought the Second World War, but was at the same time fundamentally different from it. Wartime expansion had been orchestrated primarily through the recruitment of inexperienced civilians into the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR) — the ‘Wavy Navy’, so-called because of the distinctive pattern of the officers’ rank braid — and because the majority (but certainly not all) of RCNVR personnel tended to serve in the small ships of the ‘corvette navy’. With the wartime imperative to crew vessels as quickly as possible, training was kept to the minimum required for safety, and operational effectiveness suffered as a result.[15]

That changed in the last two years of the war, by which time RCNVR officers were commanding virtually all of the frigates and corvettes fighting the Battle of the Atlantic, and to very good effect. The corollary that has entered the popular historical memory, however, is that the permanent-force RCN abandoned this anti-submarine war to the RCNVR, in preference to developing a ‘big-ship’ fleet of aircraft carriers and cruisers that would constitute the post-war navy. In truth, there was a great crossover: experienced pre-war RCN officers commanded the River-class destroyers that oversaw the convoy escort and support groups, and RCNVR officers and ratings were a major part of the complements of those big ships that operated during the war. More to the point, when the RCN was reduced to a strength of fewer than 5,000 all-ranks in 1946, because of wartime deaths and other dismissals of pre-war ‘regulars’, this in fact reflected an infusion of nearly 4,000 RCNVRs into the post-war force. Improving the ‘basic’ standard of readiness of these officers and men in itself would have rationalized the dedication of the RCN to the training function described above; the recruiting of another 5,000 all-ranks to reach the authorized post-war establishment made it imperative.

A detailed study of the social composition of HMCS Crescent, the destroyer that suffered the incident in Nanjing on 15 March 1949,[16] underscores the enormity of the changes in the RCN. Among other points, the distinguishing feature of the ship’s company was its youth. Out of a complement of 14 officers and 187 ratings borne for that cruise, the median age was 22.5, with the youngest being 18.5, and only four were over 35 (including both the coxswain and the chief engine room artificer; the captain was only 31). Only 13 ratings had served in the pre-war RCN, while fully half (94) had joined since war’s end; among the officers, only the captain and the two gunners had joined before the war, and the two sub-lieutenants were the only ones (like the captain) who had undertaken comprehensive professional training in the Royal Navy. Translating this into another vague gauge of credibility, of all the senior appointments on board, hardly anyone had more than eight years in the service, fewer than half could claim any truly pertinent wartime experience (especially in destroyers — most were corvette men), and only the captain had filled his present capacity before.

The context simplistically given in The Mainguy Report was flawed in yet another respect. Contrary to the impression developed that the breakdown in discipline in 1949 was an isolated event, it was in fact part of a pattern of low-level disobedience that had been practiced in the RCN at least since the mid-1930s, probably picked up by sailors who were frequently rotated (like their officers) for training with the Royal Navy. Because so few ratings in the post-war RCN had served in that period, it is difficult to point to a direct transfer of such knowledge, but the circumstantial evidence that Canadian sailors had been exposed to it is overwhelming.[17] Importantly, that ‘tradition of mutiny’ was well known, understood, and accepted by all ranks throughout the fleet.

The massed expression of protest in the Royal Canadian Navy invariably took the form of lock-ins, or ‘sit-down strikes’ as the service’s official historian, Gilbert Tucker, styled them.[18] These were spontaneous displays, precipitated by some local event, and undertaken with a view to attracting the attention of immediately superior officers to a problem the sailors believed was within the power of those superiors to correct. The precise cause for protest varied. Most commonly it was conditions of over-work, less frequently it was over issues of welfare specific to the ship (such as food and leave), and occasionally it was in reaction to the intemperate actions of the captain. Only once did the sailors aim to remove the commanding officer (and in that case the captain was clearly unstable), and on only one other occasion did the crew refuse to sail (for convoy duty, but again under a captain in whom they had lost their confidence).

Invariably, large numbers of a ship’s company would join together to voice some collective complaint for which there was no other officially sanctioned form of expression. Importantly, their officers recognized the restrictions under which the men operated and appear to have accepted the lock-in as an acceptable form of protest. If the men’s demands were at all reasonable (and they usually were), they were acted upon, promptly and without recrimination. No member of the RCN was ever charged with mutiny. The only persons who appear to have earned any significant time in cells were the men who had disobeyed wartime sailing orders. Certainly, no one ever was awarded the punishment stipulated under King’s Regulations for the RCN (KRCN) for mutiny — death by hanging.

None of these ‘incidents’, either in 1949 or those preceding them, involved ‘the violent seizure of a ship from her officers on the high seas’, a display which, according to one naval historian, ‘may be said to belong to the Cecil B. de Mille school of history’.[19] Indeed, the author of that statement, Nicolas Rodger, demonstrated that such incidents ‘were virtually unknown in the [Royal] Navy’. Instead, ‘collective actions by whole ship’s companies ... did happen, and happened quite frequently’.[20] The tradition of mutiny in the Canadian Navy, as such, was very much in keeping with that of the Royal Navy, from which the RCN derived so much else of its heritage.

Having established the incidents of 1949 and the reaction to them as part of a larger pattern, it is time to turn to the substance of The Mainguy Report. Fifty years on, we have lost sight of the fact that very few of the observations and conclusions in it came as a surprise to contemporary officers or politicians. In fact, large portions of it were an almost verbatim repetition of the findings of an internal study into ‘Morale and Service Conditions’ conducted by the Naval Staff and presented in the fall of 1947 to the minister[21] — the same Brooke Claxton who would receive The Mainguy Report two years later. Discontent had been widespread that summer, mostly over the issue of pay. The Mainguy Report referred only to the August 1947 incident in the cruiser Ontario, but there had also been recent incidents in the destroyers Nootka and Micmac and at the fleet schools in Halifax and Esquimalt. Besides the immediate transfer of Ontario’s executive officer, the more widespread unrest precipitated significant pay raises that fall and again in 1948. In the time-honored tradition of the RCN, the men had obtained redress of their grievances.

With the immediate problems of 1947 resolved, the Naval Staff could turn to the more important task of dealing with the underlying issues. The requirements identified in the ‘Morale and Service Conditions’ study ranged from the necessity for adequate quarters (shipboard, barrack, and married), through better pay to be made more equitable among the various trades and branches, to films to be shown at sea, the start-up of a ‘lower-deck’ magazine, the standardization of new entry training, the Canadianization of officer training, and the better application of the divisional system.[22] The majority of these being budgetary considerations, the Chief of the Naval Staff (CNS), Vice-Admiral Harold Grant brought the four main items to the attention of the Minister: pay, service accommodation, married quarters and travel warrants (rail passes for long leave home).[23] Claxton’s response is not recorded, but his own depth of concern for the plight of the sailors can be adduced from the fact that travel warrants (made popular during the war but dropped as a peacetime cost-cutting measure) were not reinstated, only a handful of new married quarters were built over the next several years (the number was especially low in comparison to the other services), no new naval barracks would be constructed until late in 1953 (and then only as part of the general Cold War expansion), and the general pay raise was driven only by the imperatives of tri-service equality.[24]

Grant was essentially left to his own devices. Within the strictures of his budget and the physical capacity of the small staff at Naval Service Headquarters (NSHQ), he moved swiftly and effectively. The divisional system already was described in the KRCN and further bureaucratization of that process evidently was deemed unnecessary. However, a message ordering the institution of welfare committees in all RCN ships and establishments had been promulgated the week before the incident in Ontario. When in the fall of 1947 the Naval Staff looked at re-commissioning HMCS Sioux, one of several destroyers held in reserve, the preparatory refit was mandated to include the popular American-style cafeteria messing and the fitting of bunks instead of hammocks.[25] The number of ratings commissioned from the ranks was increased dramatically through 1948, and plans were made to reopen the wartime training establishment HMCS Cornwallis as a dedicated new-entry training center. The fleet still was too small to offer any alternative to officer and specialist training with the Royal Navy, but 40 cadets from the naval college HMCS Royal Roads were embarked in Ontario for the spring cruise of 1948.[26] The glossy naval newsmagazine Crowsnest appeared in the fall of 1948. It was immediately popular for its chatty stories of happenings in the fleet, but also contained solid information on directives from NSHQ and the implementation of the various reforms.

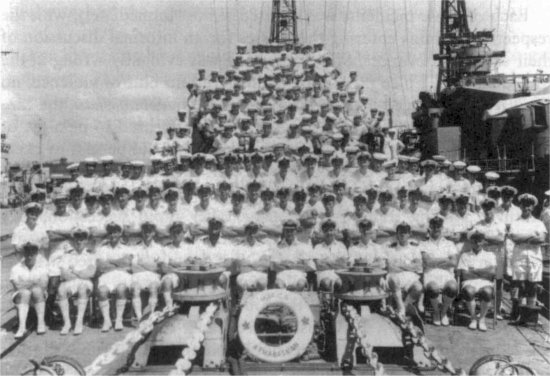

|

2. Athabaskan’s ship’s company a month after the incident, officers seated in front. Note the high number of ratings with peaked caps (chiefs) as opposed to those in regular sailor rig. (Source: National Archives of Canada) |

It is possible to conclude, therefore, that the Morale and Service Conditions Study undertaken in the fall of 1947 accurately identified many of the underlying sources of discontent in the RCN, and that within months a great many of its recommendations were being implemented. The measure of its effectiveness is that retention and recruiting both improved considerably. Moreover, extensive research has not uncovered a single reference to any sort of incident in the Canadian fleet between that in HMCS Ontario in August 1947 and the three in 1949 reported upon by the Mainguy Commission. These developments were not the signs of a service in distress, as the RCN had been in the summer of 1947.

Other than the critical but expensive capital issues of shore accommodation and married quarters, there remained only the requirement ‘to re-examine the trade group structure as applicable to the Navy’. Admiral Grant had promised to do so in his note to the Minister, and prominent among the staff action undertaken through 1948 was a fundamental reorganization of the navy’s rank and trade group structure to bring it in line with the establishment and higher pay rates of the army and air force. This was to be effected essentially by splitting the petty officer and chief petty officer rates into new divisions each of 1st and 2nd class. Then, all present leading rates were to be promoted to the new rating of petty officer 2nd class, present petty officers with less than three years seniority would become petty officers 1st Class, and so on.[27] Some stokers grumbled about seamen now gaining the equivalent of their higher technical specialist pay, while seamen resented the promotion of engineering branch members without the requisite leadership responsibilities or capabilities, but the new structure came into effect on 1 February 1949 to general approval.

There was, however, at least one unintended consequence. The social analysis of Crescent reveals that, in aggregate numbers, the restructuring resulted in a temporary, unforeseen change in complement from the authorized 42 chiefs and petty officers to a new total actually embarked of 62, with a commensurate drop in the number of junior ratings from the authorized 150 to 125.[28] Quite literally, there were suddenly too many chiefs and not enough seamen to perform the myriad of shipboard tasks.

In the rigidly hierarchical world of a warship’s lower deck, this was clearly a disruption to the established order of shipboard life. When Athabaskan had to conduct a fueling in Manzanillo on 26 February 1949, there were too few junior hands to accomplish this labor-intensive undertaking in the humidity, heat, and primitive surroundings of that port. On top of it all, the executive officer had not yet authorized a change to ‘tropical routine’ (with the workday compressed into the 6:00 a.m.—12:00 noon time period, ending before the heat of the day), and the morning’s fueling was to be followed by a full afternoon’s work.

One of the able seamen who struggled with the lines and hoses that morning had been involved in the incident onboard Ontario in August 1947. He maintains the only connection between the two events was the sudden, overwhelming feeling of frustration at ‘what was viewed as an unreasonable work environment or treatment’.[29] An ill-conceived order from the executive officer, ‘to put [their] caps on straight’ and off the backs of their heads, was sufficient contributing cause to set 90 men in Athabaskan to barricading themselves in their mess decks after lunch.[30]

It is easy to envision a similar set of circumstances attending Crescent alongside a rain-swept jetty in Nanjing, China, the morning of 15 March. Through the previous night, the duty watch had found itself with too few hands to respond to a numbing sequence of misadventures: humping cases of beer for the British embassy ashore to the jetty and then back on board when the lorry failed to appear; replacing the gangplank when it was washed away in the swollen Yangtze current; standing extended sentry guard duty over the ship and the canteen ashore against looters and other hazards of war. The able seaman who would be the ringleader of the incident the next morning told the Mainguy Commission that, ‘we asked [the] PO2 ... to ask the coxswain if he would put us in two watches, as it was too much for the small watches we had’, but no action was taken on the request.[31] The next morning, faced with the prospect of humping the beer back to the jetty yet again, 83 men responded to the call ‘out pipes’ by locking themselves into their mess.

In both cases, the sailors enjoyed immediate resolution of their demands. Although neither executive officer was sacked, the men did obtain the direct intervention of their captains to address their plight. Athabaskan sailed from Manzanillo the same afternoon, but immediately thereafter assumed a tropical routine. The duty watches in Crescent were revised, and greater attention was paid to organizing recreational activities ashore. Divisional officers and chiefs and petty officers in both ships adopted a more active interest in the welfare of their men. Just as important, no retribution followed. The Mainguy Report records that charges of slackness were laid against certain of those involved in Athabaskan: ‘Each case was heard and those who had no reasonable excuse were cautioned’, although, as the commissioners further observed, ‘Caution is not a punishment.[32] In Crescent, the Captain heard requestmen, and the most discomfort anyone had was summoning enough courage to face his commanding officer.

The incident a few days later in Magnificent demands re-examination. Where the sailors in Athabaskan and Crescent had been unaware of the other’s actions, those in the aircraft carrier were fully cognizant of the earlier incidents and their apparent success at no personal cost. On the morning of 20 March 1949, the early call to ‘Flying stations’ at 5:30 a.m. was postponed because of suddenly adverse weather conditions. The men were advised they would be piped again at 8:50 a.m., but in the meantime should follow their regular routine, which included breakfast and then falling in to clean ship at 7:45 a.m. The description in The Mainguy Report of what followed is most revealing:

|

3. Admiral Mainguy in a messdeck with some Canadian sailors. (Source: National Archives of Canada) |

At ‘out pipes’ (0740), the chief petty officer in charge of the aircraft handlers noticed that the only handlers on the flight deck were leading hands. He sent a petty officer [2nd class] below to see what was wrong. The petty officer reported the men were not coming up .... The chief petty officer then went below and found the men sitting around their mess deck in silence. When he asked them if they were coming out he received no reply .... The state of affairs was reported to the Captain. He proceeded to the mess deck .... At the time of the Captain’s visit [at 8:10 a.m.], all ratings present in the mess were then employed in scrubbing out their mess deck. This work, which would have been part of the normal duty of most of the men after 0745, was well advanced.[33]

This ‘incident’ in Magnificent was nothing of the same scale or intent of those in Crescent or Athabaskan. It most likely would not have occurred but for the inspiration of the actions in the destroyers. In the tradition of mass protest in the RCN, it most certainly would not have received any attention outside the ship were it not for the interest already provoked by the others. There is evidence that this copy-cat incident is more properly understood as the result of personal differences between the executive officer and the air commander — and, indeed, that it would not have figured in the deliberations of the Mainguy Commission but for previous bad blood between that same executive officer and one of the commissioners.

The wonder, then, is that only three ships experienced incidents and not the entire fleet. Again, the rank and trade group restructuring offers a plausible explanation. As most of the new senior rates were to be employed at shore establishments, the new structure was never intended to have a major impact upon ships’ complements, other than some minor adjustments to ensure all required branch and trade group positions were filled. The temporary increase in the numbers of senior rates in ships would be balanced in short order by the ‘drafting’ or posting process. This is what happened with the navy’s east coast ships, which did not sail until early March, giving time to effect the changes while still in home port. The west coast ships, however, had sailed at the end of January and had to implement the changes at sea with the existing ships’ companies and no infusion of replacements. Compounded by the absence of functioning welfare committees in Athabaskan and Crescent, the result was, if not predictable, at least understandable.

Intent, however, on exposing the breakdown in relations between officers and ratings, The Mainguy Report completely overlooked this fundamental structural problem, restricted as it was to the lower deck. It is surprisingly easy to demolish the further charges in The Mainguy Report as to the lack of a Canadian identity in the RCN, the preference of its officers for British ways, the inadequacy of their training in the Royal Navy, and the alleged collapse of the divisional system.

Brief examples must suffice. Crescent had been dispatched to Nanjing by the Canadian government precisely for the ‘prestige’ of having its own warship on the scene, and while otherwise indistinguishable from the other British vessels on the station (or the Australian for that matter), the ship proudly displayed standardized maple-leaf emblems on her funnel (the commission reported that they had been removed).[34] Instead, for all the fuss made in the Report over ‘Canada badges’ (i.e. shoulder flashes), not one sailor providing testimony to the commission raised that as an issue critical to them, although when queried by the commissioners as to whether it was a good idea, they of course agreed.[35]

As for the divisional system, evidence from the quarterly reports placed in the personnel records of Crescent crewmembers show that it was indeed an institutionalized practice, but a pattern did emerge in that succeeding reports on any individual were invariably written either in a different unit or by a different officer. This suggests that the commission’s attribution of the collapse of the system to the poor training of officers was only in part true: while junior officers schooled in the Royal Navy had a very good understanding of the working of the system, the ex-RCNVR officers had had only minimal exposure to it during the war. Rather, the breakdown was due more to the frequent turnover of personnel of all ranks through different ships and establishments as they rotated through training billets – a connection the commission failed to make.[36]

One of the committee’s better findings was the lack of functioning welfare committees in the three affected ships. Certainly, those would have allowed a more effective form of internal communication to possibly defuse tensions. But because the rank and trade group restructuring issue was restricted to the lower deck, the ineffectiveness of welfare committees could only have been a contributing, not a causal, factor of mutiny. Because records from that period were not always carefully preserved, it is impossible to determine whether such committees existed in the other ships of the fleet, and whether this played a role in their being spared any unrest.

The question remains: why should the memory of events a half-century past be so very wrong? There are any number of institutional, political, and even petty personal reasons for this to be so. The main problem, however, is probably historiographical — the entire period between the end of the Second World War and the outbreak of the Korean conflict is poorly remembered and understood for practically any service, Canadian or Allied. Peacetime military administration and bureaucracy is rarely a compelling avenue of investigation. For the five short years, 1945-50, researchers generally have found it convenient to acknowledge briefly the retrenchment associated with post-war demobilization before progressing into the ‘real’ history of the Cold War, starting with the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949. In Canada, the diplomatic history of the period has been well covered,[37] but, for the RCN, effectively the sole available source has been The Mainguy Report.

For all of the attention devoted to this document, however, it has never been subjected to rigorous analysis. Two important considerations have been overlooked: first, the otherwise common acceptance that officially sanctioned commissions of inquiry obfuscate as much as they expose; and, second, the general condemnation with which naval officers of all ranks greeted the publication of the report. Not all of these latter misgivings can be dismissed as the ranting of men feeling too personally the sting of its findings.

It is worth noting that Claxton expressed satisfaction in his memoirs with The Mainguy Report, making the self-serving claim that ‘The whole tone strengthened my hand regarding modernization of the treatment of personnel and the further Canadianization of the Navy.[38] The Chief of the Naval Staff (CNS), however, had identified many of the problems plaguing the naval service and recommended solutions to the minister in October 1947. Although Claxton was not forthcoming with the funds required, other than for the immediate expedient of pay, the Naval Staff was nonetheless able to move ahead on other fronts, including a fundamental reorganization of the lower-deck rank and trade group structure. Following the rash of desertions and lock-ins of 1947, there were no incidents in the RCN through 1948. Given the progress advanced in so many areas in spite of continued government parsimony, it is possible to conclude that The Mainguy Report did not strengthen Claxton’s hand but rather forced him to follow through on the remaining money matters it also identified. That Vice-Admiral Grant was not fired on the strength of such a damning report can be explained only by the fact that the Minister knew his CNS (Chief of Naval Staff) could have brought him down, too. For Grant — ever the stoic archetype of his service — there was perhaps enough in the grim satisfaction of finally obtaining the appropriations needed to rebuild the post-war navy.[39]

The strains of demobilization and the restructuring of the new peacetime naval establishment were far more severe than has been appreciated by subsequent generations. Having discovered perhaps too easily that there were no communists in the RCN, the commission presumed to expand its mandate to find problems between officers and the men. The apparent breakdown in officer—man relationships, culminating in the incidents of 1949, was far more complex than can be explained by simply fixing blame upon an uncaring officer corps steeped in British ways. But the Mainguy Commission’s politically driven imperatives blinded it to reporting on conditions that were extant two years previously (in 1947) and obscured the subsequent reforms.

None of this is to say that the Mainguy Commission and subsequent Report were a wasted exercise. Sometimes the obvious needs to be stated. After the spring of 1949, the Canadian government could no longer ignore the deprivations that peacetime cutbacks had imposed on the naval service. Within the fleet, no one of any rank could any longer claim innocence of the implications of group insubordination. Nor could they sanction the informal resolution of such action, or be indifferent to welfare committees and the divisional system. Proof of this came swiftly. In early June 1949, even as the Commission still was hearing testimony, a group of junior hands in the frigate HMCS Swansea — incensed at poor treatment by their commanding officer — locked themselves in their mess. The response was a forceful entry by armed troops, a rapid court-martial of the senior hands, and their sentencing to 90 days’ hard labor and dishonorable discharge from the navy.[40] There seems not to have been any similar trouble since.

The ‘incidents’ in 1949 were really only that — discrete events, and not symptomatic of the widespread discontent that indeed had existed earlier. Rather, they fit the pattern of a larger ‘tradition of mutiny’ that extended to other Commonwealth navies. If they were unique in any way, it was in hastening the end of that tradition — at least in Canada — through the exposure of a formal investigation and an object lesson in the importance of modern grievance resolution practices.

NOTES

with the object of providing machinery for free discussion between officers and men of items of welfare and general amenities within the ship or establishment that lie within the powers of decision held by the Captain or his immediate Administrative Authority ... They will not repetition not be entitled to discuss questions of welfare or amenity outside the ship nor will they be entitled to deal with conditions of service, e.g., discipline, pay, allowances, leave scales, etc.