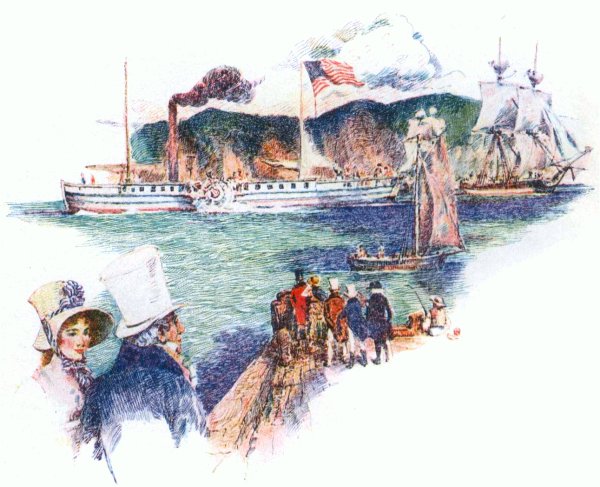

Steamboats of the Great Lakes.

The North River Steamboat, often named the Clermont.

From: Fred Erving Dayton, Illustrated by John Wolcott Adams, Steamboat Days, New York, Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1925, 402-411.

Ninety thousand square miles of the Great Lakes, stretching 1,555 miles in length, remained a transportation waste until 1797 when the first American schooner was launched, and with no outlet to the South or Atlantic coast the number of craft increased slowly. A steamboat was built on Lake Ontario in 1816, and in 1819 Walk-in-the-Water, 340 tons, was launched at Buffalo. Trinkets and supplies were carried westward, the steamers returning with furs and peltries, being mostly trade with Indians. A new order was created with the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. Western New York threw off its frontier aspect and became an exporter of goods, a receiver of produce, and the base from which adventurous pioneers set out for the new West.

Steam tonnage multiplied to transport growing commerce. Superior was launched in 1822, another steamboat in 1824, two in 1825 and three in 1826. The first voyage upon Lake Michigan was made in 1826, a pleasure excursion, and then in 1832 business called, and a Government steamboat reached Chicago, carrying supplies for the Black Hawk War. Lake tonnage reached 14,381 tons in 1841 and by 1850 had jumped to 58,711 tons and in 1860 to 108,243 tons, one-half of which was registered out of Buffalo, one-third from Detroit while Chicago had 8,151 tons in 1860 and none before.

The 11 steamboats running in 1833 carried 61,485 passengers to and from Buffalo and fares and freight receipts totalled $229,212. This was the year of the great land speculations when crowds streamed West. Three trips were made each year to the Upper Lakes. From Buffalo to Chicago and return required 25 days, the round-trip to Detroit was 10 days in making, reduced to three days for paddlers and five days for propellers in 1851.

Lake commerce was controlled by an association owning 18 steamboats in 1834, ruling until 1841 when it then owned 48 vessels. The Ohio canals opened up a great grain country to the lakes and in 1835 Ohio exported, by water routes, 543,815 bushels of wheat; increased to 3,800,000 bushels in 1840 and in 1 851 reported as 12,193,202 bushels, paying $500,000 in freights, and then in the '60's upwards of 26,000,000 bushels of wheat streamed across the lakes in ships. Enormous bulk freights, largely wheat and ore, have continued to be moved by lake steamers in the navigation season, and a type of vessel developed specially adapted to lake transportation.

The opening of the Ohio Canal in 1833;the Illinois Canal in 1848 and the Indiana Canal in 1851 added to the transported produce, and railroads, when they were extended were feeders in creasing the lake trade. The size of vessels, their greater speed when under way, and the greater dispatch in loading and unloading by modem power, permitted the same quantity of tonnage to do ten times the business. Lake steamers averaged 435 tons in 1859 and in the '60's side-wheelers averaged 68o tons and 478 tons for propellers. Lake freighters of less than 4,000 tons became unprofitable against 6,000 and 7,000 ton steamers, while Col. James M. Schoonmaker is 8,603 gross tons, 590 feet length, 64 feet beam, 34.2 feet depth of hold, with engines of 2,500 horse power.

Great Lakes traffic had increased in 1914 to 185,000,000 tons and Buffalo received 190,143,327 bushels of grain and 9,312,114 barrels of flour. The tonnage passing through Detroit River, reported by Army engineers, showed an average for the ten years, 1904-14, of 33,000 passing vessels of 55,000,000 registered tons, carrying cargoes of 70,000,000 tons valued at approximately $800,000,000.

The change from side-wheelers to propellers began in 1843 with the building of Hercules, 275 tons, at Cleveland, and in 1851 there were 52 propellers on the lakes of 15,729 tons. The number had increased to 118 propellers of 55,657 tons in 1860 and while these early propellers had less speed they gained in favour for their economy of fuel until they came to almost monopolize lake traffic.

Walk-in-t he-Water was built by Noah Brown at Black Rock (Buffalo) in 1818. The crosshead engine was built by Robert McQueen, New York. James B. Stuart, Nathaniel Davis, John Mads, Robert McQueen, Alexander McMuir, Noah Brown and Samuel McCoun were owners and the new steamboat left for Detroit August 25, reached in 44 hours and 10 minutes, and continued to run to Detroit, with occasional trips to Mackinac and Green Bay for three seasons, and then went ashore in a gale of wind and was wrecked near Buffalo, November 1, 1821. Papers were surrendered the following April when Walk-in-the-Water was broken up and the engine recovered and installed in Superior in 1822. The engine had long life, for some of its parts went in Waterloo, a third hull, which was lost in 1846.

Hundreds of lake steamboats were built, for the short season made business heavy in the months of open navigation. Wooden hulls continued many years, even after iron had been introduced in Merchant in 1862. Wood was available and cheap. Gradually a type of lake freighter was developed, long, high-sided craft, with power plant located aft, pilothouse and living quarters forward and a series of compartment holds between the ends.

Some of the early outstanding lake steamers were Michigan, 1833, whose two beam engines afterwards went in R. R. Elliott and City of Sandusky; Thomas Jefferson, 1834, whose engine went in Louisiana and was lost in her in 1858 ; and Empire, the first lake steamboat to measure more than 1,000 tons. Empire was built in 1844 at Cleveland by Captain George W. Jones and was 200 tons larger than any other vessel in the world, fast and splendidly appointed. Empire ran many years between Buffalo and Toledo and was converted to a propeller latterly.

Princeton, a twin screw propeller, was built in 1845, the first with an upper cabin. The twin engines were built at Auburn, N. Y., State Prison. Princeton ran in a fleet of 14 passenger steamboats, connecting Buffalo and Chicago. Atlantic, built by J. L. Wolverton, Newport, Mich., in 1848, was 267 feet length, with engine by Hogg & Delamater, New York, was chartered to run between Buffalo and Detroit with Mayflower and Ocean, in connection with the Michigan Central Railroad, running on the route 1849-52. Atlantic's end was a Great Lakes tragedy, being run down by Ogdensburg off Long Point, Canada, August 20, 1852, sinking in 15 minutes. Of the 420 passengers and crew 150 persons perished. Atlantic held the speed record, Buffalo to Detroit, 16 1/2 hours, and was the favorite steamboat of the times.

Mississippi ran between Buffalo and Sandusky with St. Lawrence, and was new in 1853, going out of commission in 1859 and laying up at Detroit until 1863 when deck houses and furnishings went into a new hull, named Racine. Mississippi's engine was brought to New York and installed in Guiding Star.

Western World and Plymouth Rock were sensations in 1854, designed by Isaac Newton, whose Hudson River steamboats were famous, and built by John Englis & Son, Brooklyn, who brought a trained force to Bidwell & Banta's Buffalo yard and the Allaire Works, New York, built the engines. Each ship measured 2,000 tons, 348 feet length, 45 feet beam, 72.6 feet over guards, and 15 feet depth of hold. The engines had cylinders 81 inches diameter by 11 feet stroke, rated 1,500-horse power, and the wheels were 38 feet diameter.

These were the finest steamboats on the Great Lakes and were built by the New York Central and the Michigan Central Railroads to ply between Buffalo and Detroit. They cost $250,000 each and no expense was spared. Hull timbers were diagonally braced with iron, the floors were solid, and they had four watertight compartments. The saloon decoration combined Gothic, Ionic architectural motifs and there were stained glass domes and rose-wood furniture while the dining hall seated 200 persons. In the second year the boilers were moved forward, which improved them. Western World made Detroit from Buffalo in 14 hours and Plymouth Rock was even faster. After a few seasons both boats were laid up at Detroit for several years and broken up. Western World was dismantled at Buffalo, and the engine went in Fire Queen, a New York steamboat.

Western Metropolis was built in 1856 to run between Buffalo and Toledo in connection with the Michigan Southern and Northern Indiana Railway, and had iron paddle wheels and made 21 miles' speed, being dismantled in 1862 and made into a barque, then carrying 65,000 bushels of grain, spreading 5,000 yards of canvas and was never beaten under sail. Western Metropolis was lost in Lake Michigan in 1864. The engine had been first installed in Empire State, and when removed was taken East and installed in a steamboat of the same name.

Milwaukee and Detroit were built in 1859 and were the only ocean type of side-wheelers to come on the lakes. They were designed by H. O. Perry and were built by Mason & Bidwell at Buffalo, being 247 feet length, 34 feet beam and 1 7 feet depth of hold. They ran between Milwaukee and Grand Haven. Milwaukee was lost, October 9, 1868 entering Grand Haven harbour in a gale, but no lives were lost.

Merchant, built at Buffalo in 1862 by David Bell, was the first iron propeller on the Great Lakes and ran between Buffalo and Chicago for J. C. & E. T. Evans for 13 years. Merchant ran on Racine reef, October 8, 1875, a total loss. Ironsides, built at Cleveland in 1864, while running out of Milwaukee, struck on Grand Haven bar, September 14, 1873, and foundered ten miles off shore. Passengers and crew took to boats, but 24 lives were lost.

Greyhound had a jumbled history, being first Northwest, built at Manitowoc in 1867 and 248 feet length, 32 feet beam, 54 feet over guards, with engine having cylinder 6o inches diameter by 12 feet stroke, and was built for the Goodrich Transportation Company to run along Lake Michigan western shore. The engine came from the old Planet, dismantled in 1866 and had been originally installed in Canada, built in 1846, and in 1851 was installed in Caspian, which was wrecked in 1852. This same engine was set up in E. K. Collins in 1853 and when that ship burned in Detroit River in 1854 the engine was salvaged and went in Planet, which was completed in 1855. From Planet the engine went in Northwest in 1867, which later became Greyhound.

Northwest replaced Morning Star between Cleveland and Detroit in 1868, continuing until 1876 when the old engine, now worn out, was junked and the engine from Detroit, built in 1859 by the Shepard Iron Works, Buffalo, replaced it. Greyhound continued until larger and finer steamboats came to the run, when it was altered for day excursions. A new Greyhound was built in 1902 for Detroit excursion business.

Sheboygan, built in 1869 at Manitowoc, had a historic engine, built by the Buffalo Engine Works, which had previously been in City of Cleveland and Garden City. Chicago, built in 1874, inherited May Queen's engine. Another City of Cleveland, built at Wyandotte, Mich., in 1880, had an engine, built by Dunham & Company, New York, with cylinder 50 inches diameter by 11 feet stroke from United States. The cabins came from Adirondack, which ran on Lake Champlain. City of Cleveland was built for the Detroit & Cleveland Steam Navigation Company and made 19 miles speed, and afterwards ran between Detroit and Hancock on Lake Superior, and later to Alpena, being then named City of Alpena. A new line was organized to run between Cleveland and Buffalo in 1893 and City of Alpena became State of Ohio.

Oswego and Chemung, built at Buffalo in 1888 by the Union Dry Dock Company, were the finest freight propellers on the Great Lakes when they came out, 2,611 tons, 350 feet length, with triple expansion engines, and cost $350,000. The Union Steamboat Company built them to carry package freight between Buffalo and Chicago and they averaged 16 1/2 miles per hour, the fastest time that had then been made by lake freighters.

City of Detroit, one of the first of the modern passenger lake liners, was designed by Frank E. Kirby and built for the Detroit & Cleveland Steam Navigation Company by the Detroit Dry Dock Company in 1889, and cost $250,000. The Detroit Dry Dock Co. succeeded Campbell Owens & Co.; shipbuilders. The first yard on the lakes to build metal ships, at Wyandotte, Mich., was established by Stephen R. Kirby and his sons, F. A. and Frank E. Kirby, for Captain E. B. Ward. City of Detroit made 21 miles' speed, the engines being built by W. & A. Fletcher Company, Hoboken. City of Chicago was built in 1890 for the Graham & Morton Transportation Company, a passenger liner, and in the same year Frank E. Kirby came on to run between Detroit, Sandusky and Put-in Bay. Frank E. Kirby made 21 miles an hour, the engine coming from the Alaskan revenue cutter, John Sherman, having 48 inches cylinder diameter by 9 feet stroke, rated 1,330 horse power.

The first inclined beam engine was installed in City of Toledo, built in 1891 for the Toledo-Put-in Bay route, and built by the Cleveland Shipbuilding Company, of triple expansion type with cylinders 26, 42 and 6o inches diameters by 6 feet stroke. City of Toledo was used in the World's Fair trade and then came back to its route.

W. H. Gilcher, which held the record as the largest wheat carrier, 113,885 bushels, was built in 1891 at Cleveland, and foundered in a Lake Michigan gale, October 28, 1892, when all on board were lost.

Virginia, a twin screw propeller, was built in 1891 for the Goodrich lines, running from Chicago to Milwaukee, and cost $250,000, having accommodations for 300 passengers. Virginia makes 18 miles' speed. Chicora was built in 1892 for the Benton Harbor route and Manitou at South Chicago in 1893, to run between Chicago and Sault Ste. Marie. Manitou had accommodations for 400 persons and cost $300,000.

Few steamboats attracted the attention that came to Christopher Columbus, a whaleback designed by Alexander McDougall and built by the American Steel Barge Company in 1892 at West Superior, Wis., being 362 feet length, 42 feet beam and 24 feet depth of hold, the hull being divided by nine bulkheads. It was claimed for the unusual design that it combined great strength, fine appearance and roominess, but those with practiced eye for good lines found the whaleback ungainly above the water line. Christopher Columbus carried thousands of passengers in World's Fair time and has been successful in the years since. In the 1923 season, while tied up in Milwaukee, it was struck with a great weight, falling from a high building, but sustained slight damage.

It remained for James J. Hill to bring out the finest steam vessels on the Great Lakes, Northwest and Northland, built for the Northern Steamship Company to run between Buffalo and Duluth. Northwest came out in 1894, being built by the Globe Iron Works, Cleveland, 383 feet length, 44 feet beam, 25 feet depth of hold and 4,244 tons, with twin screws driven by engines of 7,000 horse power. These vessels cost $650,000 each and had accommodations for 350 first-class and 300 second-class passengers, and carried no freight.

Great Lakes speed records are claimed for Theodore Roosevelt, a day liner running from Chicago, built in 1906 at Toledo, 275.6 feet length, 40 feet beam, 23.4 feet depth of hold, with 5,000 horse power. United States, in the same line, was built in 1909 at Manitowoc, being 193 feet length, 41 feet beam and 16 feet depth of hold. United States was purchased by Col. E. H. R. Green and was used several years as a yacht on the Atlantic coast, going back to Lake Michigan in the former service in 1923. Tashmoo, in excursion business from Detroit, was built at Wyandotte in 1900 and is 302.9 feet length, 37.6 feet beam, 13.6 feet depth of hold and rated 3,150 horse power.

[For some large liners running from Chicago, Detroit, Toledo, Cleveland and Buffalo see second page.]

Eastland, carrying a day excursion of Western Electric Company workers from Chicago, July 24, 1915, turned over in Chicago River, and 812 excursionists were drowned.