The Defence of Canada In the Light of Canadian History

by Christopher West

Author of Canada and Sea Power

J.M. Dent, London and Toronto, 1914

[text starts page 3][1] It was in the spring of 1865 that four men sailed from Canada to England as commissioners to confer with the Imperial authorities on the defence of Canada and on other matters. The conference on defence arose out of correspondence during the preceding four years, which showed that the Imperial Government not only expected that Canada would contribute more men and money to build up military power in British America but that such contributions should be made permanent and independent of local parliamentary control. The Duke of Newcastle, the Colonial Secretary, who carried on the correspondence with Lord Monck, then Governor-General, recommended to the Canadian Government some "new form of taxation apart from customs duties," and advised that for the development of this new military policy "its administration and the supply of funds for its support should be exempt from the disturbing action of ordinary politics," and he even had the method ready at hand when he suggested that the money should be taken out of the Consolidated Fund and voted for a period of years to "remove the military question from the arena of party politics."

This was an early essay towards the co-ordination of the forces of the colonies under a control centralized in London, which in various forms has been under the searchlight of discussion for the past three years. But then there was an emergency - not an emergency arising out of the contingencies of war on distant shores, but an emergency begotten of the sight of armed enemies on the very borders of Canada and of threats whose execution would make a carnage ground of the spreading grain fields of these young Provinces.

The danger of war between Great Britain and some European nation, or between Great Britain and the United States, involving Canada in the conflict, was greater in 1865 [page 4] than in 1914. Apart from the legacy of ill-will born in the American Revolution and sedulously treasured in the school literature of the United States, in which England was represented as the tyrant of the world, there were the dangers from boundary disputes and trade disagreements such as arose out of the fisheries regulations.

The Trent affair was an example of the reality of these dangers. In 1861, in the first year of that fratricidal conflict in the United States, two commissioners, Mason and Slidell, sent by the Confederate States to represent the Southern confederacy in Great Britain, were forcibly taken off the steamer Trent on the high seas by United States Captain Wilkes. The North went wild with excitement and Wilkes was everywhere hailed as a hero. Without exception, almost, the press and members of Congress endorsed his action. The War Secretary, speaking in the lower house of Congress when a vote of thanks was passed to Wilkes, praised his "brave, adroit and patriotic conduct." When the news reached England there was a demand for an instant release of Mason and Slidell, and while troops were ordered off to Halifax, orders were given to place the navy and arsenals on a war footing. It did not lessen the danger to remember that the United States itself had declared war on Great Britain in 1812 in resisting similar acts of searching peaceful neutral vessels, or that Great Britain also was reversing her attitude on the right of search question. What saved the two nations from war was that Queen Victoria's husband lay dying, and in his last hours counselled Her Majesty to such delay and moderation of the demand that the United States had time to recover its reason and comply without loss of self-respect. But the Trent affair, and the idle boastings of the press of both countries, tended to alienate the sympathies of the Canadian people from the Northern cause, while the incident of the seizure of two United States vessels on Lake Erie by Southern desperadoes and the raid on the Vermont border at St. Albans by Southerners helped to embitter the feeling of Americans.

No sooner had these dangers begun to disappear, as the bloody drama of the Civil War reached its final acts, than the mysterious threats of the Fenian invaders came to disturb the peace of the Canadian people. And on top of all this the threat to abrogate the reciprocity treaty with its disturbance of friendly trade. Here were reasons why Canada should develop a strong military policy. A militia commission had been investigating the defence of Canada and in 1861, urged by the home authorities it recommended that to provide for the defence of the country the active militia force should be raised to 50,000 men with a reserve of the same number. This proposal was brought before the Legislative Assembly but the bill was thrown [page 5] out on its second reading. An appeal was made to the country and the opponents of the bill were endorsed in the new election. The Government were satisfied to maintain the powers of the old militia law under which the Governor-General was authorized to call out the militia "in case of invasion or imminent danger of the same."

Such was the situation when these four commissioners went to confer with the Imperial Government on the question of defence. They reported at Quebec in July, 1865, and upon their report was based a memorandum prepared by the Executive Council in reply to the proposals of the Imperial Government. In beginning the report the council referred to "the disturbances on the Canadian frontier, the imposition of the passport system, the notice given by the American Government for the termination of the convention restricting the naval armaments on the lakes and other events which tended to revive the feeling of insecurity," and they admitted that "the position was further complicated by the formal notice given by the American Government to terminate the Reciprocity Treaty in March next."

They pointed out to the members of the British Government that "while fully recognizing the necessity, and while prepared to provide for such a system of defence as would restore confidence in our future at home and abroad, the best ultimate defence for British America was to be found in the increase of her population as rapidly as possible, and the husbanding of our resources to that end; and without claiming it as a right, we venture to suggest that by enabling us to throw open the North-west Territory to free settlement and by aiding us in enlarging our canals and prosecuting internal productive works, and by promoting an extensive plan of emigration from Europe into the unsettled portions of our domain, permanent security will be more quickly and economically achieved than by any other means."

The council showed how this might be done without cost to the British exchequer, and how it might actually lighten the burden of defence about to be assumed by the people of Canada. They said the expenditure for militia had increased recently from $300,000 to $1,000,000 a year, and they agreed to train a militia force "provided the cost did not exceed the last mentioned sum annually, while the question of confederation was pending." With regard to the recommendations of the Duke of Newcastle the council pointed out that the preceding Parliament had rejected the military commission's scheme as "extremely distasteful to the country" not only on the ground that "the method of enrolment was highly objectionable" but because it established military machinery "at [page 6] variance with the habits and genius of the Canadian people and entailing an expenditure far in excess of the sum which the legislature and the people have declared themselves willing to provide." They added that the rejection of the measure was the result "not of party combination but of a deliberate conviction that its principle was unadapted to the occasion, obnoxious to the Province and that the financial resources available for military purposes were unequal to the outlay." In their opinion volunteer organization alone was suited to the country, and there was "a decided aversion to compulsory service." Moreover, "the people of Canada are doing nothing to produce a rupture with the United States and having no knowledge of any intention on the part of Her Majesty's government to pursue a policy from which so dire a calamity would proceed, are unwilling to impose upon themselves extra burthens. They feel that should war occur it will be produced by no act of theirs, and they have no inclination to do anything that may seem to foreshadow, perhaps to provoke, a state of things which would be disastrous to every interest in the Province. On this ground their representatives in Parliament rejected the proposal to organize 50,000 men or even to commit the Province to a much smaller force, and the recent elections, embracing more than one-third of the population, have shown that public feeling has undergone no change."

His Grace had suggested "a basis of taxation sounder in itself than the almost exclusive reliance on customs duties," but the council did not think it would be prudent to impose direct taxation for military purposes and they believed that "no government could exist that would attempt to carry out the suggestion of His Grace for the purpose designed."

His Grace had expressed the opinion that by increased military preparations the credit of Canada would be improved, but the council contended that not the least important consideration was a due regard to the means at the command of the Province, "and they hold that they are more likely to retain the confidence of European capitalists by carefully adjusting expenditure to income than by embarking in schemes beyond the available resources of the Province. They are prepared to expend money on the Intercolonial Railway and similar works, but they are not prepared to enter upon a lavish expenditure to build up a military system distasteful to the Canadian people, disproportionate to Canadian resources and not called for by any circumstances of which they at present have cognizance."

As to taking the control of funds from the domain of Parliament, "popular liberties are only safe when the action of the people restrains and guides the policy of those who are invested with the power of directing the affairs of the country. [page 7] They are safe against military despotism wielded by a corrupt government only when they have in their hands the means of controlling the supplies required for the maintenance of a military organization."

Such is a summary of a state paper remarkable for its correct interpretation of the peaceful aspirations of the Canadian people and equally remarkable for its stout resistance to the theory then current that national credit and international influence were solely to be measured in terms of military force. It was remarkable, too, in the time and circumstances of its preparation, for the imagination of Canadians had already been stirred by the movement for the federation of the eastern Provinces with Canada and the prospect of the acquisition of the vast domain held under the rule of the Hudson's Bay Company, and even the early extension of the Dominion to the shores of the Pacific Ocean. If ever there was a time when a people might have been forgiven for glorying in their connection with an imperially minded people and in making a display of the symbols and attributes of military power it was at this time and with such a prospect before them.

Who, then, were these four commissioners who refused to assume that a nation's neighbor should be its permanent enemy; and who foresaw in the multiplication of thrifty homes of intelligent people a greater strength in time of trial than in the hired soldier whose dominance leads to despotism?

Let them stand forth to the gaze of the Canadians of 1914.

The first of the four whose name is signed to the report is John A. Macdonald, the first Premier of the new Dominion, who could nevertheless say in his closing years, "A British subject I was born; a British subject I will die."

The second of the four is George Etienne Cartier, the French-Canadian patriot who is reported to have said that the last shot fired in defence of British liberties in Canada would be fired by a French-Canadian. And let it not be forgotten that he himself was the first Dominion Minister of Militia.

The third is George Brown, the champion of the people's rights, an unselfish zealot in the cause of representative government, who was great enough to lay aside the sword of the disputant that the people of every Province and race might be one.

And the fourth to complete the square in this cornerstone of statesmanship was Alexander T. Gait, the first builder in the economic policy of united Canada.

But Sir John A. Macdonald, Sir George E. Cartier, George Brown and Sir A. T. Galt had another mission besides that relating to Canadian defence when they went to England in 1865 and that other mission was to plan the basis of the confederation. [page 8] Thus the framers of the new constitution made it clear that in building the national foundation they had determined to give to a war-cursed world a pledge of good-will to every people, and not to obtrude upon their sight those means of doing ill deeds which so often make ill deeds done. It was a time of provocation towards Canada, but can we now doubt that Canada's amity towards her neighbors had its influence in the peace which reigns between the British and American peoples to-day?

Upon this foundation what kind of a superstructure are the Canadian statesmen of the present generation raising?

Take the matter of expenditure. In 1868, while the excitement and provocation of the Fenian raids of 1866 were fresh in mind, the amount spent on the militia and gunboats was $960,940, or including the military stores and properties taken over from the Imperial Government, $1,481,861. It also included the cost of the conversion of the Snider-Enfield rifles, the cost of the military survey of Canada, and the balance of pay to volunteers during the Fenian raids. Of this total the amount estimated for drill sheds, rifle ranges and targets was $110,000.

In 1869 the total cost of the militia and gunboats and pensions was $1,058,832, of which $50,000 was for armories and $17,225 for pensions.

In 1894, twenty years ago, and three years after the death of Sir John A. Macdonald, the entire cost of the militia, including the fortifications of Esquimault [sic], was $1,284,517. This did not include the pensions, which were $25,409, but it included the amounts spent on the series of barracks for the North-west Mounted Police (about $20,000), which is not a military force but in reality a civic police force.

The estimates for 1914, just laid before Parliament, show an expenditure for the militia and defence department of $10,867,000 and for the naval service of $2,460,000, making apparently a slight reduction on the cost of the previous year.

This appearance of reduction is found on analysis to be misleading, for an investigation of the details of these estimates reveals that the following amounts are chargeable against the military and naval expenditure, making the grand total about four million dollars more than last year.

| Militia and Defence Department | $10,867,000 |

| Naval Service Department | 2,460,000 |

| Total barracks, drill halls, armories, ordnance buildings, etc., under head of Public Works | 2,530,000 |

| [page 9 begins] Naval buildings, under Public Works | 1,000,000 |

| Drydocks, Naval | 1,500,000 |

| Extra placed under "Civil Government" | 186,900 |

| Extra under Naval Service | 144,300 |

| Military branch of pension list | 104,181 |

| ------------- | |

| Grand total | $18,792,381 |

As an example of the perpetual apparition of new waste and self-stultifying expenses that pursue the nation bent on naval dominance the following paragraph from last year's report of the naval service is noteworthy: "Since the machinery and plant at the dockyards [Halifax] were installed by the Admiralty entirely new developments have taken place in engineering, resulting in the introduction of turbine machinery for propulsion in practically all new warships" and consequently the plant and shops are entirely inadequate.

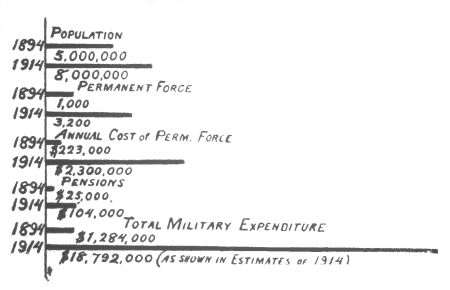

Put in the more easily comprehended form of a diagram [2] the record of military expenditure in Canada in the past twenty years is as shown below :-

1894 5,000,000

1914 8,000,000

1894 1,000

1914 3,200

1894 $223,000

1914 $2,300,000

1894 $25,000

1914 $104,000

1894 $1,284,000

1914 $18,792,000 [AS SHOWN IN ESTIMATES OF 1914]

The reader will see that while the population of Canada has increased by less than one-half in the two decades, the number of the permanent force has increased three times, and its annual cost over ten times. The military pension list has increased four times, and the total military expenditure fifteen times.

If these are the whips with which we are beginning to [page 10] chastise ourselves to maintain the "random boast and foolish word" of national pride, what will the scorpions feel like when our administrators have devised a "permanent naval policy".

Between the present period and the formative years of the Canadian confederation there are some notable contrasts, not only in regard to the cost of these military establishments as shown but in the general attitude of responsible public men towards military questions.

It will be observed, first, that though the war spirit had been excited by the events before mentioned and by the terrific conflict in the United States, and though at the very time when the memorandum to the British Government was being prepared in 1865, preparations were known to be afloat for the Fenian invasion of Canada, the leaders of both political parties and of both races in Canada were united in their aversion to militarism. Their words were almost a paraphrase of the logic of Cobden when he said: "It is a common error to estimate the strength of a nation according to the magnitude of its armies and navies; whereas these are the signs and, indeed, the causes, of real poverty and weakness in a people." The founders of the Confederation carried their belief into practice in spite of alarms and actual emergencies. No sooner were the Fenian raids over than the ordinary expenditure on militia and gunboats dropped to $960,940 (1868). After the first Riel rebellion the cost of the militia and permanent force dropped to $667,000 in 1881; and while it rose to $2,707,758 in 1885 owing to the second North-west rebellion, it fell again in 1886 to $1,178,659. When the invaders had been driven back or rebellion put down, the people were encouraged to go back to their peaceful labor, as the Hebrews were divinely instructed to do after like dangers were over. Up to the close of the nineteenth century there is no instance where a recognized leader of public opinion urged the people to apply themselves to the study of destroying human life as a means of securing the happiness and prosperity of their country. Within the past few years, however, thousands of leaflets and bulletins have, for the first time in the history of this country, been issued at the public expense with the object of teaching our young men the value of the art of killing their kind. Systematic efforts are being made to Europeanize our institutions of learning, from the universities down to the public schools, and inducements are held out to teachers, ministers of the gospel, Y. M. C. A. workers and others to bring the weight of their leadership to make the children believe that the drill and trade of a soldier will "uplift the manhood of the nation. [See "Memorandum on Cadet Corps Training, by the Minister of Militia," "Notes on the Relative Cost of Criminal Statistics and Liquors and Tobaccos, Compared with the Cost of the Militia Force of Canada," [page 11] etc. Another writer will explain by what means and to what extent this propaganda is being directed to poisoning the healthy fountain of life in our educational systems and what a brood is being now hatched for the coming generation to combat.]

The second feature of contrast between the policy of the fathers of confederation and recent administrators is that the former not only set their faces against the adoption of the European system of standing armies for Canada, but confined this defence within Canadian territory and by the Canadian people. The "Permanent Militia" of Canada was limited by law and common understanding to 1,000 men and that restriction was not overstepped till after the death of Sir John Macdonald. In violation of his policy the "permanent force" has become a standing army of over 3,000 at a yearly cost which has swelled from $223,000 in 1894 to over $2,300,000 in 1914; and visitors to Ottawa who meet the uniformed orderlies and officers at every turn can judge whether the pomp of military rule is growing or diminishing. The leaders of both parties were united in opposing the efforts then made to glorify the soldier's trade, and they resisted the pressure exerted in the name of loyalty to tax the people with needless military establishments.

A third point to be noticed is that while the leaders of both parties were united on this policy of peaceful development and patient reliance on the influence of good will, the actual temptations to develop the military spirit were overwhelmingly greater and the dangers of war involving Canada were more frequent and more real than now. Leaving out of account the disputes between Great Britain and the United States arising out of the fisheries and the boundaries questions, Canada had two border raids and two rebellions in this period when weak administrators would have yielded to the military pride and national feeling thus excited.

Now, in one of those strange declensions by which our political leaders seem bereft of the sagacity that had earned the confidence of the past generation, the people are being urged to run down the steep place into the sea at a time when the forces of international good will are becoming more manifest than ever, when the failure of physical force becomes more patent as the European military system begins to break of its own deadly weight, and when a conquest of Canada is a danger no more substantial than a mirage of the desert.

What we should understand by the recital of this history is that the faith of Sir John Macdonald, George Brown and Sir George E. Cartier in the ultimate triumph of intelligence and gentleness over ignorance and national pride, has been completely justified in the present amicable relations between Great [page 12] Britain and the United States and Canada. Even if we had not the analogy of European states to judge by, where one nation is adding to its burdens through the suspicions raised by its neighbor's preparations for possible war, we know that if past Canadian governments had interpreted the occasional display of American passion to be the permanent attitude of the American people and had increased our military establishments on the plea of securing our defence, Canada could not possibly have been more secure if the United States had reciprocated such a policy in kind. The mutual good will of Canada and the United States is beyond all calculation in monetary value.

The most precious legacy left by these builders of Canada was therefore that first proclamation of defence policy which, in direct opposition to the Imperial theories then current, was based upon faith in the ultimate friendship of the United States; and if the greatest asset in British foreign policy today is the good will of the American nation, Great Britain has these Canadian statesmen to thank for it.

Now let the people of Canada and the leaders of the people make no mistake - this foundation is in danger of being destroyed. If the reader will again study the extracts from the great state paper before quoted he will see that the principles laid down by Sir John A. Macdonald and his contemporary statesmen were both simple and reasonable, namely, that Canada should not create a standing army, that her defence should be by her own citizen soldiers and that that service should be confined to our own soil. It was clearly a corrollary that Canada should not interfere by force in affairs outside her own territory or be made responsible for Imperial policy over which the Dominion had no control.

It seems fairly clear that as far as Sir John himself was concerned his judgment was based on two considerations. One was a sympathetic regard for the temper of the French-Canadian people. They have been traditionally a people who, loving liberty and peace themselves, respect the liberty and peace of other people. The other was that the policy of non-interference was reasonable and wise in itself, and, to paraphrase his own expressions, the peopling of the land with an intelligent, contented and lightly taxed population was a better defence for Canada than to create those means of offence which under a heady or corrupt administration are as likely to make trouble for a country as to safeguard its holier interests. Whatever his reasons those were the principles upon which he and the other founders of this confederation agreed. It would have been well for Canada if the contents of this memorandum had been more generally known and its wisdom set forth with more zeal, for the statesmen who prepared it well knew that to force the [page 13] French-Canadian people beyond the line of defending their own land from aggression was an elemental wrong, not merely to them but to humanity at large. Had their sentiments been studied with a little more insight and sympathy the debacle of national pride by which this country was swept from its feet during the Boer War would never have occurred. As Lord Salisbury and many other public men realized that England "put her money on the wrong horse" when the Crimean War was entered on, so we Canadians of British origin are beginning to realize that in the Boer War something went wrong - that a wind was sown which may yet be reaped as a whirlwind. The later developments of the German naval policy can be as clearly traced to the Boer War as any other cause and effect, and this in turn has started Canada on the vain quest of "sea power" - that realm of national hypnotism out of which the people of Canada will one day awake to find themselves in the grip of the same kind of armament interests that are now so well represented in the legislation and the policy of Great Britain.

And so the reaction goes on while the bills, in various forms, are coining in for the people to pay. In financial cost alone the tree is bearing pretty heavy fruit already. For several years preceding the Boer War the expenditure of Canada on military affairs was about $1,500,000 a year, and but for Canada's first war of aggression that sum would have been more than ample to-day. But the excess of cost due to that departure makes a total up to this year of over $62,000,000, and the "permanent policy" has not yet been announced.

It is the writer's belief that if the conscience of the Canadian people were laid bare the true convictions of the people in 1914 would confirm, and not deny, the principles of defence laid down in 1865. It is because the frothy elements, carried away by race pride and passion, have so warped and perverted the sober sense of the people, that men are scared to utter these convictions. The responsible leaders of the two parties are afraid of this froth and noise, and therefore permit this counterfeit loyalty to pass as genuine coin. So fearful are the political leaders that every man has more of this counterfeit coin than genuine money in his pocket, that they are afraid to tell the people they must get back to a sound money basis. And so it happens that when the truth seeker asks for light, the party politician, if he is a Liberal, will tell him the salvation of the country depends on a navy built in Canada; if a Conservative, the seeker will be warned that the British Empire will fall if a contribution of $35,000,000 is not handed over to be spent by the armament rings who are sitting on the backs of the British taxpayers. In other words, so long as the party shibboleths are correctly pronounced, it seems immaterial whether the basic principles of self-defence [page 14] founded in self-government laid down at Confederation are maintained or not.

Ignoring these principles, each party magnifies its own method, and their methods are both on a false foundation, if Macdonald, Brown and Cartier were right.

In another work ["Canada and Sea Power"] the writer has discussed the question of war and the modern movements making for international co-operation, and has endeavored to show the unique opportunity Canada, of all nations, has in leading in this movement towards international good will. If Canada is now to be carried away by the fallacy of "sea power" she will be self-disqualified from taking this lead and her grand opportunity will be lost.

The illusory notion which it suits the big-gun firms, the warship firms and other armament firms so well to perpetuate is that it is necessary for Great Britain to be supreme on the ocean. It can be demonstrated that in the sense in which it is meant to be understood it is now impossible for any one power or even a group of powers to dominate the ocean, to the extent of destroying or even suspending the peaceful commerce of the world, for the reason that too much of the world is now civilised and in absolute need of maintaining peaceful trade and the whole earth would cry out against such an outrage. A hundred years ago the marine trade of the world practically centred on England, now scores of nations have direct commerce with each other which does not pass through British ports at all, and this new distribution is increasing every year. The fact is that the only part of the seven seas which Great Britain can effectively "dominate" are the home waters immediately surrounding the British Isles, Great Britain is no longer supreme, even in the Mediterranean - as Admiral Mahan, the father of the "sea power" fallacy - himself admitted the other day in a letter to a London paper.

If Great Britain agreed to the immunity of peaceful private shipping in war time - in conforming with the universally recognized rule on land - then the safety of Canadian, Australian, South African and all other commerce at sea would be assured under international law; but at the last Hague conference the British Government declined to agree to a proposal to which two-thirds of the nations represented were favorable. Among these was Germany, and when we remember that two-thirds of all Germany's foreign trade is sea-borne can one wonder that that nation felt justified in safeguarding her coasts by the same means which have been pleaded for the "supremacy" of the British navy? The moment Great Britain agrees to exempt peaceful ships from seizure that decree will automatically free Canadian ships of commerce from danger, and [page 15] hence there will be no need of a Canadian navy, except for offensive purposes, which are against the traditions of the Canadian people. Even if Canada could stand the tremendous cost of creating an effective navy, there would be no real safety in a British-Canadian fleet under a British naval policy so long as that policy is directed, as in fact it is, by the armament syndicates who are so well represented in Parliament and in the affairs of the Admiralty and who take their huge profits with Imperial impartiality out of friend or foe - Briton or Turk, republic or empire, Canadian or South American, civilized or semi-savage. While this usurpation of representative government continues in Great Britain there is nothing but danger in any naval adventure of Canada, for given a premier of the temper and disposition of Lord Palmerston, and any man with a match may cause an explosion that will incarnadine the seas. On the day when the British Government takes the control of warship construction out of the hands of private firms and makes it a Government monopoly it will be in order to consider a Canadian navy on the same plan.

We have heard the argument that Canadians are bound to this dangerous naval departure because Great Britain has spent huge sums in the past in planting and defending the colonies all the world over. Is this argument not carried a little too far? No one will deny the bravery, the enterprise and the public spirit of thousands who have led in planting colonies and carrying good British institutions over the world, but in the main is it not the cold fact that British trade at home was promoted by British trade abroad through these developments - in short, that British colonies were formed, maintained and protected because it brought material advantages to the country that planted them. If the people of one generation are bound to consider themselves under a mortgage to another people because of what was done by a past generation that obligation must go beyond mere national boundaries. The present British people themselves are admittedly under a debt to the Romans for the basis of their law as well as their good roads, but does this put the modern Briton under obligation to contribute to the octroi of Italy, or even to the Italian navy.

The British people are indebted to Greece not only for much of their culture but for an invaluable element in the strength and grace of the English language itself, but this debt, which is a real and living one still, did not influence the British armament companies or the British Government very powerfully, seeing that they have just sent a commission to reorganize the Turkish navy in order that it might deal more effectively with the navy of Greece. For its laws, its institutions and its language and literature the United States owes just as much to Great Britain as Canada does and perhaps at bottom there is [page 16] much admiration and respect for the old land in that country as in this, but do the American people recognize any obligation to contribute to the upkeep of the British law courts or the British navy? Is it not more sensible to think, as most of us will think on reflection, that each generation of civilized men is born into the world inheriting all the labors and enlightenment of all past generations, and this inheritance is free to all who can avail themselves of it, with only the duty of adding to and improving upon these gifts and with only the responsibility that pertains to their own brief day.

In the light of this responsibility for our own acts is it not bad enough that we have wandered so far from the high road of safety and moral progress marked out for us with such wisdom and foresight by the founders of this confederation? Why should we - out of a theory of loyalty which our great fathers knew to be false - and told us so in plain language - deliberately place on the backs of our children a load of the kind that is breaking the backs of the common people of Europe and taking the heart out of their lives. Let us not deceive ourselves - since the science of human government was first developed the advent of the professional soldier in government has been the source of waste of material resources, of the corruption of civic life and in the end the weakening or destruction of the people's liberties. When men say that education in the art of destroying human life is necessary to "uplift the manhood" they deceive themselves, for the highest authority to whom universal man can appeal has described militarism in a phrase which all the reiteration of nineteen hundred years has failed to deprive of its graphic awfulness and fidelity to the abhorrent fact - "the abomination that maketh desolate."

Notes:

[ Back ] Footnote 1: [16pp] credit Library and Archives of Canada microfiche, Mic.F. CC-4 c.2 #84557

[ Back ] Footnote 2: this table was in fact a hand drawn image in the original: